New Garden Township

Chester County, Pennsylvania.

The Isaac and Margaret Sharp House as it appeared in the early 20th Century

Cynthia G. Falk

1996

(Revised 2004)

|

Cynthia G. Falk

completed research on the Isaac and Margaret Sharp House

in 1996 while a student in the Winterthur Program in

Early American Culture. The project was undertaken as

part of a course in vernacular architecture at the

University of Delaware taught by Bernard Herman, who

suggested the building as the topic for study. After

finishing her master’s degree at Winterthur, Cindy

completed a Ph.D. in the American Civilization Program at

the University of Delaware. She is currently Assistant

Professor of Material Culture at the Cooperstown Graduate

Program, an M.A. program in history museum studies

co-sponsored by the State University of New York College

at Oneonta and the New York State Historical Association.

Today Cindy works with her students to document and

preserve locally significant architectural resources. Cynthia G. Falk

completed research on the Isaac and Margaret Sharp House

in 1996 while a student in the Winterthur Program in

Early American Culture. The project was undertaken as

part of a course in vernacular architecture at the

University of Delaware taught by Bernard Herman, who

suggested the building as the topic for study. After

finishing her master’s degree at Winterthur, Cindy

completed a Ph.D. in the American Civilization Program at

the University of Delaware. She is currently Assistant

Professor of Material Culture at the Cooperstown Graduate

Program, an M.A. program in history museum studies

co-sponsored by the State University of New York College

at Oneonta and the New York State Historical Association.

Today Cindy works with her students to document and

preserve locally significant architectural resources. |

When James Crossan described the house of the late Isaac Sharp as "nearly new" in 1841,1 the core of the building had already stood for half a century. Since its construction in 1782, the dwelling had provided shelter for multiple generations of the Sharp family. It had also undergone significant changes. What began as a sizable but coarsely finished log structure had been enlarged and profoundly improved.

The original appearance and subsequent transformation of the Isaac Sharp house raise numerous questions about the relationship between materials, scale, and finish in late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century domestic architecture. The Sharp house is one of a limited number of eighteenth-century log structures in the Delaware Valley that still exist in the early twenty-first century. Beneath multiple layers of improvements, the building maintains a level of finish that, even if common in the eighteenth century, is an exceedingly rare survival two centuries later (figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Isaac and Margaret Sharp House (New Garden Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1782) as it appeared in September 2003. The vine-covered frame structure (to the right) and the front porch are later additions.

Figure 2. First-floor plan of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house as it existed in 1996.

Because of its unique characteristics, the Sharp house provides a fascinating comparison with the area's other surviving eighteenth-century houses, which are predominantly well-finished, multi-storied, and stone. As a sizable domestic structure that was associated with an established, prospering family, the Sharp house does not seem out of place. However, when its un-hewn log shell and poorly finished interiors are considered, it is clear that the Sharp house did not conform to period notions of refinement. Its original occupants, Isaac and Margaret Sharp, chose to live in a house that was unassuming and old fashioned. Unlike other family members, they turned their backs on gentility as expressed through material possessions, as well as leadership roles in the community and occupations other than agricultural labor.

The history of the Sharp house begins with the history of the land it occupies. The 94 acres associated with the house in 1841 were situated predominantly in New Garden Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. However, a small section of the "plantation" jutted into neighboring London Grove Township. This portion of the property was originally part of a 60,000-acre tract that was granted to the London Company in 1699.2 The remainder of the acreage was part of William Penn, Jr.'s portion of the Penn family's Stenning Manor.3 Although the London Company and William Penn, Jr. were the first owners of the land, Joseph Sharp was probably the first European occupant. In 1714, Sharp purchased two separate 200 acre tracts from William Penn, Jr.'s share of Stenning Manor. The western-most of these two tracts included a portion of the White Clay Creek. Joseph Sharp later acquired an additional 100 acres, which adjoined the western side of this White Clay Creek tract (figure 3).

Figure 3. Detail from “Lands Around London Grove Meeting, 1700-1730,” map drawn by Gilbert Cope, 1914. Based in part on early eighteenth-century survey of New Garden Township. On the map, Joseph Sharp’s three tracts in New Garden and London Grove Townships are clearly delineated. Cope’s map and the original survey are currently in the collection of the Chester County Historical Society library, map file for New Garden Township.

Until 1723, Joseph Sharp was taxed as a landholder in New Garden Township, Chester County. In that year, however, Sharp was one of 22 petitioners to request the formation of a new township, to be known as London Grove.4 The line that would divide London Grove from New Garden Township also divided Sharp's 100 acre tract to the west of the White Clay Creek from the 200 acre tracts he bought from Penn. Since Joseph Sharp was subsequently taxed as a landholder in London Grove, and was made an Overseer of the Poor in that township,5 it can be assumed that he was residing on his London Grove property.

Figure 4. Joseph and Mary Sharp house (London Grove Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania). The core of the building is dated 1737. The kitchen addition (to the left) dates to 1811.

Figure 5. Joseph and Mary Sharp house, datestone on main house.

Joseph and his wife, Mary (Pyle) Sharp, constructed a large, two-story, stone house in London Grove Township in 17376 (figure 4 and 5). When Joseph Sharp, "of the township of London Grove," wrote his will in 1746, he bequeathed this house and "all this Plantation whereon I now Live Containing three hundred acres of Land with all the houses [,] out houses [,] Barn [, and] Tan yard Part thereof In the township of the said Newgarden and part In the township of London Grove" to his young son Samuel Sharp. Because Samuel was not of age, his uncle Samuel Pyle was to "have the Care of him and Bring him up and give him Education and Put him to Some trade as he may think fitt."7

Samuel Sharp had reached the age of majority by the year 1757, when he married Mary Starr, widow of Isaac Starr and daughter of Richard and Abigail (Harlan) Flower.8 Like his father, although Samuel Sharp owned land in both London Grove and New Garden townships, he was consistently taxed in London Grove until 1782. In that year, Samuel Sharp's name was added, out of alphabetical order, at the very end of the landholders portion of the New Garden Township list for the Pennsylvania state tax. Samuel was assessed in New Garden for 80 acres and an "improvement." This reference to an "improvement" is the first official record of the "nearly new" house described in 1841.

Figure 6. Isaac and Margaret Sharp house as it appeared in 1996.

Samuel appears to have constructed the two-story, log house (figure 6) for his newly married son and daughter-in-law, Isaac and Margaret (Johnson) Sharp.9 In 1783, while Samuel continued to be enumerated in London Grove Township, his son Isaac took his place in the New Garden Township tax records. In New Garden, on the banks of the White Clay Creek, Isaac occupied 80 acres of land and a dwelling. He lived there with two other individuals10-presumably his wife Margaret and his young daughter Lydia.

Ten years after the Sharps were first taxed in New Garden Township, Samuel and his wife Mary were able to break the entail on Joseph Sharp's will and sell a portion of their property fee simple to their son Isaac. Because Joseph's will specified that his plantation was to be inherited by Samuel Sharp "and the heirs of his body Lawfully Begoten for Ever,"11 the Chester County Court of Common Pleas had to approve the division of the real estate for fee simple purchases. In 1792, after the Court's ruling, Samuel and Mary sold 100 acres to Isaac and 60 acres to their son-in-law James Jones.12

Isaac Sharp continued to reside on the property he purchased from his parents until his death in 1825. At that time, according to Isaac's will, his wife was given "use of the farm...during her widowhood." In order to avoid the inheritance problem his parents faced, Isaac stipulated in his own will:

I Give & bequeath unto my son Isaac Sharp all my farm situate part in New Garden & part in London Grove Townships, to him his heirs & Assigns to take possession of as soon as his mother[']s right ends. With privilege for my said son Isaac Sharp to sell so much of the land at anytime he may choose after my decease to pay the Just debts & to make a Deed or Deeds thereof....Provided my said son should die in possession of All or part of said farm without leaving lawful issue to survive him, to lawful age to heir it, then it is my will that the same by sold & equally divided among all my children or their representatives.13

The second Isaac Sharp did not choose to divide or sell his father's farm. At the time of his death, in order to fulfill the requirements of the first Isaac Sharp's will, the "plantation" was sold pursuant to an order of the Orphans' Court of Chester County and the proceeds from the sale were divided between the surviving children and grandchildren of the first Isaac Sharp.14

With this sale, the "nearly new" house and 94 acres of land did not immediately pass out of the Sharp family. The estate was purchased in 1841 by the first Isaac Sharp's unmarried brother, Joseph Sharp. However, Joseph Sharp never occupied his brother and nephew's log house. Rather, he continued to live in the nearby 1737 stone house, which his grandfather, Joseph, had built, and he had inherited from his father, Samuel.

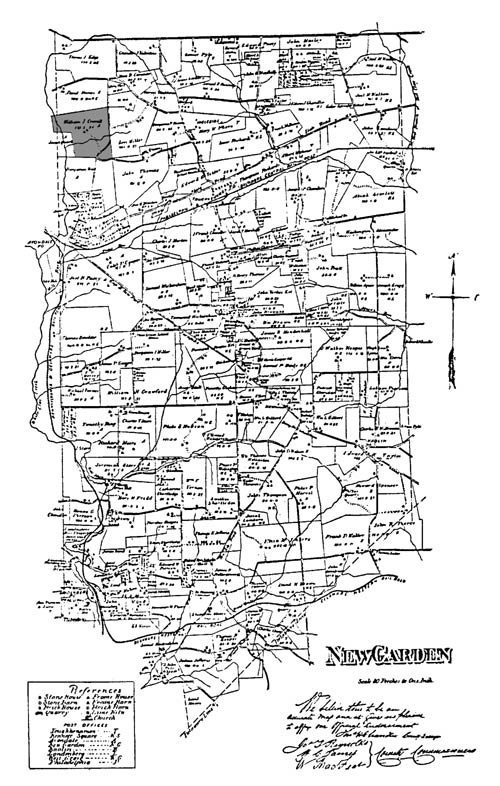

When Joseph Sharp died in 1847, he bequeathed "all that tract of land which I purchased at public sale of the administrator of Isaac Sharp" to his grandnephew Vincent Quarll.15 In 1862, Quarll, who was "of Philadelphia," sold the property, complete with a mortgage debt of $1000 and two other liabilities totaling $4500, to Kickwood and Clarkson Moore.16 The following year, the Moores sold the still heavily mortgaged estate to Pemberton Moore. Pemberton Moore farmed the property until 1878, when he sold it to Philadelphia attorney, William J. Crowell17 (figures 7 and 8). Because of a heart condition, Crowell planned "to 'retire' and raise his family" on the rural Chester County property. The original Isaac and Margaret Sharp house and a portion of the surrounding acreage remained in the Crowell family until 1972.18

Figure 7. Detail from map of New Garden Township showing Pemberton Moore’s holdings. From Atlas of Chester County, Pennsylvania, From Actual Survey by H. F. Bridgents, A. R. Witmer and Others (Safe Harbor, PA: A. R. Witmer, 1874).

Figure 8. Map of New Garden Township showing William J. Crowell’s holdings. From Breou’s Official Series of Farm Maps, Chester County, Pennsylvania, Compiled, Drawn, and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys (Philadelphia: W. H. Kirk and Co., 1883).

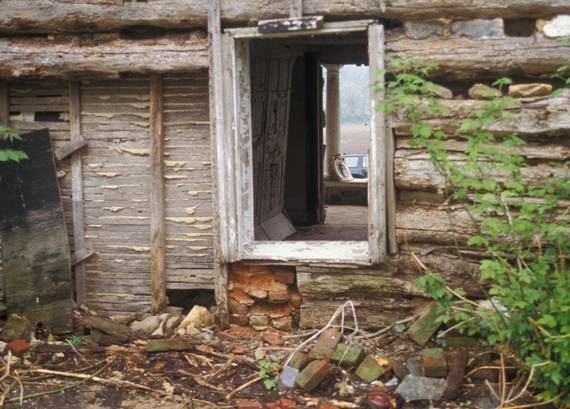

In 1996, when research for this paper was conducted, the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house stood unoccupied. After the Crowell family sold the house in the 1970's, new owners made plans to level the antiquated structure. Although a complete demolition was never realized, all of the stucco was removed from the exterior of the building and the rear half of a nineteenth-century addition was razed (figure 9). Much of the original log structure and the framing of the surviving portion of the addition remained without windows or sheathing to protect them from the elements. To the rear of the structure, where the removal of part of the addition left a gaping hole, damage had been catastrophic. From the exterior, the interior spaces of all three stories of the addition and parts of both stories of the original log building were visible.

Figure 9. Rear view of Isaac and Margaret Sharp house with subsequent additions.

Because of the Sharp house's poor condition, many of the original features of the structure, which were subsequently covered by layers of plaster and stucco, were discernable once again. Limited destructive investigation, involving the removal of plaster and lath, as well as later floorboards, permitted other elements to be revealed19 (figure 10).

Figure 10. Bernard Herman and Gabrielle Lanier removing plaster and lath in an attempt to find evidence of a staircase leading from the first to the second floor of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house.

As originally constructed, the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house was a two-story structure, with a partial cellar below and a garret above. The building was assembled of logs, many of which were left in the round (figure 11). These logs were layered in alternating tiers and joined with V-notches (figure 12). The ends of the logs, which were tapered to accommodate the notched joint, extended slightly beyond the ends of the building. The spaces between the logs were chinked with a variety of materials including stones, strips of wood, and mud. Later, bricks were used to refill some of the larger gaps between the logs (figure 13).

Figure 11. Detail from fašade of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Shows both the round and the very roughly hewed logs used to construct the building.

Figure 12. View of visible gable end of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Alternating tiers and V-notch joinery are visible at the corner of the building.

Figure 13. Detail of rear of Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Illustrates several chinking materials including wood, mud, and later brick.

The first-floor fašade of the original log portion of the Sharp house was composed of three asymmetrical bays (figure 14). The middle bay housed a door, which was framed with heavy timber members that had been pegged into the ends of the surrounding logs (figure 15). The two outer bays were fitted with small, glazed sash windows. To the left of the door, the lower edge of one window was situated a little over two and a half feet from the top of the stone foundation wall. The window to the right of the door was significantly higher, commencing at roughly four feet from the top of the foundation wall (figure 16). Like the door opening, these window openings were probably cut into place after the building had been assembled.

Figure 14. First-floor plan of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house showing original room arrangement and fenestration. Although the partition between the common room and parlor may not have been an original part of the plan, it was certainly a very early addition. The location of a door in this partition, which would have provided the only access to the parlor, was not located during field work in 1996. The location of the original stair is also unknown.

Figure 15. Front door opening at Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. The vertical wooden member is pegged into the surrounding logs.

Figure 16. Front door opening at Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Original small window opening with later door and larger window openings to left and right. The original window was covered over when the new larger window was added.

The rear wall of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house also incorporated a door and at least one other first-floor window. These were located side-by-side and roughly corresponded to the door and one of the window openings on the front facade of the building (figure 17). A second first-floor window opening on the rear wall probably paralleled the second window opening on the front wall. Unfortunately, the portion of the first-floor rear wall that would have accommodated this second rear window was missing when field work was conducted in 1996. As a result, no physical evidence remained of the window's existence.

Figure 17. Detail from rear of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Originally, this area consisted of a door-window combination. The window was located to the right and is still evidenced by a vertical piece of window framing. The door was located to the left and is evidenced by the brick in-fill and a notched area in the lowest surviving log. Both the door and window were later replaced by a single larger window.

One other original first-floor window opening did survive. It was located on the one visible gable-end wall. This small, square window (figure 18) was located toward the back of the structure and was intended to illuminate a pantry situated to the rear side of the first-floor fireplace. On the opposing gable-end wall, because an addition was later added, it was difficult to know whether any original window opening still existed.

Figure 18. Detail from visible gable-end of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Small window opening that would have provided light in a first-floor pantry.

With the exception of the attic flooring, which had been covered, all of the original floorboards at the Sharp house were removed. Many of the joists that supported the first floor of the original portion of the Sharp house had also been replaced. The one surviving original first-floor joist was simply a large log, approximately a foot in diameter, which was installed without being hewn or even having the bark removed (figure 19). This original joist contrasted with those that supported the second floor. These joists, which initially would have been visible from the first floor, were hewn so that they were almost square and were spaced at approximately three-foot intervals. They originally extended past the front of the building and supported a pent roof. Rather than being replaced at a later date, smaller supplementary joists were simply installed between them (figure 20).

Figure 19. Surviving original joist in the cellar of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house.

Figure 20. Detail of joists projecting through the fašade of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. The only original joist in this photograph is the square joist almost centered over the window. The other joists were filled in later.

Evidence of the original floor plan suggests that the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house was of one of two schemes. As first conceived, the building may have been only one room in plan. However, evidence existed in 1996 to indicate that either initially, or during the very early history of the building, a board partition was added to divide the first floor of the dwelling into two rooms arranged side-to-side in a single pile (see figure 14). The smaller of these two rooms, known during the period as a parlor, lodging room, or possibly inward room,20 was unheated and originally only accessible from the larger room. The larger room, known as a common room or hall,21 was directly accessible from both the exterior front and rear of the house. It incorporated an immense stone fireplace that was used for cooking and may have included a bake oven. To the rear side of this fireplace, a portion of the larger room was partitioned off to be used as a pantry.

The second floor of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house may have been either one or two rooms in plan. If a board partition did divide the space into two rooms, that partition was probably located directly over the one downstairs. Whether one or two rooms, the entire second floor was heated by one small fireplace, which was situated above the larger fireplace downstairs (figure 21).

Figure 21. Fireplace on the second floor of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. This fireplace may date to 1782, when the house was originally constructed.

By the time of the first Isaac Sharp's death in 1825, significant changes had already been made to the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Primarily, cooking functions appear to have been relocated outside the main core of the building. Surviving physical evidence suggested that the pantry had been removed from the larger of the two first-floor rooms. Furthermore, Isaac Sharp's probate inventory carefully divided cooking implements from other household items. While the inventory began with objects such as 13 chairs and one table, then moved "upstairs" where eight pair of sheets and four pair of pillowcases were counted, items that would have been used in a kitchen, such as kettles and pitchers, were relegated to the end of the list. The fact that "And irons[,] fire shovel & tongs" were included at the beginning of the inventory, on the same line as "Cupboard & Contents" and "Table," and that "two flat irons...[and an] Old Stove" were listed with the cooking implements, suggests that two separate first-floor flues, one for a formal fireplace and one for a cooking stove, existed by 1825.22

According to Chester County Triennial tax records, which begin in 1799, the first significant increase in the value of Isaac and Margaret Sharp's "buildings" occurred between the years 1820 and 1823. This increase probably marked the construction of a one-story kitchen, which would have been attached to one of the gable ends of a hall-and-parlor house like the Sharps'. In the Sharps' case, this kitchen probably adjoined the unheated parlor. This kitchen was eventually superseded by a larger addition on that end of the building.

The next noticeable increase in the value of the Sharps' buildings came between 1835 and 1838. The improvements made in the late 1830s were the reason that, in 1841, the 59 year-old house could be advertised as "nearly new." The most marked change was the construction of a two-story, two-bay, braced-frame addition that succeeded the earlier kitchen (figures 22 and 23). Although this structure may have begun as a single-pile addition with a kitchen space on the first floor and one other room on the second, it was later expanded to the rear to include two first-floor and two second-floor rooms.23 As a double-pile structure, the addition more than doubled the size of the house.

Figure 22. Isaac and Margaret Sharp house with frame addition built during the ownership of Isaac Sharp, son of the first Isaac Sharp. Concrete and stone room (to the right) is a still later addition.

Figure 23. Detail of area where the nineteenth-century frame addition was added to the original Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Note braced-frame construction.

At the time the addition was built, other changes were made to update the original log house. The small windows to the front and rear of the house were replaced by larger windows. The gable-end pantry window, which was no longer needed, was closed off. The rear door was removed, and a second door was added to the fašade of the original house. As a result of the new door arrangement, the old common room, the old parlor, and the new addition were all directly accessible from the front of the building.

On the inside of the log portion of the dwelling, the older random-width board partition that separated the parlor from the common room was removed. A new paneled partition was installed as a replacement (figure 24). It was relocated so that the two rooms were more equal in size. In the old common room, the large cooking fireplace was replaced by a smaller, more decorative fireplace (figure 25).

Figure 24. Nineteenth-century partition between the two first-floor rooms in the original log portion of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house.

Figure 25. Remodeled fireplace on the first floor of the original log portion of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house.

In order to unify the facades of the old log house and the new addition, a porch was added across the front of the entire structure (figure 26). Furthermore, a layer of stucco was applied over the front of the building, as well as over the rear and visible gable end of the log structure24 (figure 27). This stucco not only united the two parts of the building but also helped to conceal obsolete window openings.

Figure 26. Thomas Eakins photograph of the Crowell family on their porch, c. 1890. The porch that is shown in this picture may date as early as the late 1830s. Photo from Eakins at Avondale, p. 1.

Figure 27. Photograph of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house with its nineteenth century addition. A coat of stucco united the log and frame facades. Photo may date to the early twentieth century. Photo from Eakins in Avondale, p. 17.

On the new frame portion of the building, the lath that would hold the stucco could be applied directly over the framing members. On the older log house, the lath had to be applied over vertical furring strips (figure 28). In order to install the furring strips, many of the round logs had to be trimmed.

Figure 28. View of the rear of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. In order to facilitate the application of stucco, furring strips were applied over the log portion of the house.

After the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house left the Sharp family, still more changes were made to the structure. During the ownership of William J. and Frances (Eakins) Crowell, a studio was added to the "back of the third floor," or garret level, of the frame addition25 (figure 29). This studio was intended for Frances's brother, Thomas Eakins, who was a frequent guest of the Crowells from 1878 until 1897, when he was blamed for the suicide of the Crowells' daughter Ella.26

Figure 29. View of the rear of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house and its subsequent additions. The room that occupies the third floor (or garret) of the frame addition was designed to be Thomas Eakin’s studio.

Members of the Crowell family also constructed a one-story concrete and stone addition, which adjoined the free gable end of the frame addition (figure 30). This single-room structure, with its five large, concrete-mullioned, fixed-pane windows was probably designed as a "sun room." It included a fireplace (figure 31), whose flue ran into the larger fireplace in the adjoining frame addition, and was intended to incorporate skylights. At some point, the Crowells also replaced the old porch that ran across the fronts of the log and frame parts of their house.

Figure 30. View of the “sun room” that was added to the frame addition of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house.

Figure 31. Fireplace in the concrete and stone “sun room”—a very late addition to the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house.

By the time of the Crowells' ownership, the meager Isaac and Margaret Sharp house had been transformed to a fashionable country residence for a gentleman farmer. On the first floor of the building, the Crowells designated a kitchen, a dining room, and a music room (complete with a grand piano). The upstairs was divided into three separate bedrooms-one for Mr. and Mrs. Crowell, one for their male children, and one for their female children-and a large family or play room.27 The interiors of all of these rooms were finished with smooth plaster walls and plaster ceilings (figure 32). The music room and the dining room were heated by stoves. In the kitchen of the frame addition, although a large fireplace was included in the original design (figure 33), cooking was done on an iron range "that burned coal in the winter and wood in the summer."28

Figure 32. Plaster walls and ceiling on the second floor of the original log portion of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. The plaster on the walls and ceiling was laid over lath, which was applied to the logs and joists that first formed the visible walls and ceiling.

Figure 33. Fireplace in the first-floor front room of the nineteenth-century frame addition to the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. The masonry that projects into the back of the fireplace is part of the adjoining fireplace in the “sun room.”

This level of finish and comfort was quite different than what Isaac and Margaret Sharp had experienced when their log house was first constructed. The interior walls of that house, for example, were not originally plastered. The logs that formed the walls were simply white-washed on the interior-bark and all (figure 34). The joints that formed the ceiling were also left exposed and either painted or white-washed.29

Figure 34. Detail of the interior gable-end wall in the parlor of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. Shows white-washed logs and bark.

The Sharps were probably cooking and baking in their first-floor, common-room fireplace. In this one room, with its two small windows and two opposing doors, the Sharps and their twelve children did most of their living. Their other first-floor room, which measured only 10 by 18 feet, served as a bedroom. Upstairs, the Sharps kept, among other things, several more beds and numerous spinning wheels.30

By the time of Isaac Sharp's death in 1825, the Sharp house had already begun to be improved. Cooking functions, for instance, were removed from the common room and relocated to an adjoining structure. The pantry was also removed from the common room, and the interior log walls were covered with plaster. However, the thin plaster layer that rippled over and around each log still represented a substandard interior wall finish (figure 35). It was not until the two-story frame addition was added and the old structure was remodeled in the late 1830s that the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house was converted into a "genteel" dwelling.

Figure 35. Rear wall in the common room of the Isaac and Margaret Sharp house. The undulating plaster coat that is visible in this photograph represented a second stage of interior finish.

The question that begs to be answered is why Isaac and Margaret Sharp's house was originally finished in such a meager manner. Recent scholarly literature that focuses on log dwellings divides them into two specific groups-log cabins and log houses. In making this distinction, cultural geographers Terry Jordan and Matti Kaups cite Thaddeus M. Harris's observations from 1805, which they rephrase as follows:

"the temporary buildings of the first settlers in the wilds are called Cabins," characterized by "unhewn logs," a roof "covered with a sort of thin staves...fastened on by heavy poles," and rail chinking "daubed with mud." By contrast, "if the logs be hewed, if the interstices be stopped with stone and neatly plastered, and if the roof [be] composed of shingles nicely laid on, it is called a log-house."31

The differentiation that Harris made, and Jordan and Kaups continue to make, is that eighteenth and early nineteenth-century log structures could be either coarsely or finely finished. Coarser dwellings tended to belong to early settlers, who contemporaries typified as "Indian-like" and constantly on the move. More refined "log houses" were viewed as "permanent" and associated with a later generation of settler.

Although Harris described what he termed "log cabins" and "log houses" in the territory northwest of the Allegheny Mountains, similar observations were made about houses and settlers in the Delaware Valley. In a "letter" that appeared in The Colombian Magazine, Benjamin Rush divided the inhabitants of Pennsylvania into three groups. An individual who belonged to the first "species" Rush described was apt to live in "a small cabin of rough logs" with earthen floors and perhaps "a small window made of greased paper."32 On the other hand, the most elevated members of Rush's hierarchy tended to reside in "large, convenient" houses "generally built of stone."33

The Isaac and Margaret Sharp house does not fit conveniently into either of Rush's two extreme categories. Although the Sharp house was constructed of round logs and was very coarsely finished, the house itself was fairly large. Unlike many "log cabins," it sat on a partial cellar and contained a full second floor plus a garret. It was actually similar in plan to the hewn-log houses of Rush's "second species of settlers." According to Rush, these dwellings were usually "divided by two floors, on each of which are two rooms."34

Just as the Sharp house defies easy categorization, its owners, Isaac and Margaret Sharp, also challenge conventional classifications. Isaac and Margaret Sharp certainly did not represent the lawless, wandering settlers that both Harris and Rush associated with round-log "cabins." Isaac Sharp and his father were both born in London Grove Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Isaac Sharp's grandfather, Joseph Sharp, had come to America from Ireland in the very early eighteenth century. During his lifetime, he acquired over 850 acres of land in Chester and Lancaster counties and built himself a good-size stone house, a barn, and a tan yard.35

Isaac Sharp's father, Samuel, seems to have been as prosperous as his grandfather. Samuel inherited the family's stone house, barn and tan yard, and he followed his father's calling by becoming a tanner.36 Samuel even achieved a level of economic success that allowed him to keep servants. When one, a hatter named Patrick Mullen, ran away in 1766 and again in 1767, Samuel offered a 30 shilling reward in The Pennsylvania Gazette for his safe return. 37

With the exception of Isaac, Samuel and Mary Sharp's other children continued to share in the material prosperity of their parents. Samuel left his father's stone house to his unmarried son Joseph and his unmarried daughter Mary. While Joseph inherited the house in a legal sense, Mary was to have "the Sole use" of a first-floor bedroom, "the Sole use of the Room above the s.d Bed Room and the Sole use of the Cellar under the said Bed Room Together with Liberty to go in and out of both the Cellar Doors at Pleasure." She also was granted "the use of the Garret, Kitchen and pump in Common and Equally" with her brother Joseph.38 When Joseph died in 1847, he gave Mary the use of the estate for the remainder of her life.39

Samuel and Mary's other daughter, Abigail, had already received her share of her parent's estate when her father died in 1819. Like Isaac and Margaret, she and her husband, James Jones, were actually sold a portion of the Sharp's plantation in 1792.40 There they built (or in some way acquired) a two-story stone house (figure 36). They occupied the dwelling for only two years before they sold all their property and relocated to Illinois.41

Figure 36. James and Abigail Jones House (London Grove Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania). The datestone on the gable-end of this building reads:

I

I A

1792

Isaac Sharp's log house was a significant contrast to his brother's and sisters' dwellings. Although it shared many spatial characteristics, it lacked much of the solidity and refinement associated with well-finished masonry houses. Yet the difference between Isaac's house and other Sharp family dwellings does not seem to correspond to a notion that either Isaac's occupancy or the building itself was temporary. Although it is nearly impossible to know what Isaac and Margaret Sharp intended when they first occupied the house, it is clear that the first Isaac and then his son, Isaac, resided in the log dwelling for the duration of their lives. This sense of continuity in ownership paralleled that of the more substantial Joseph Sharp house, which was passed from Joseph to his son Samuel to his son Joseph. It significantly contrasted with that of the James and Abigail Jones' stone house, which was sold only two years after it was acquired.

Where there is a clearer divergence between Isaac and the remainder of this family is in the realm of ambition. In terms of occupation for instance, Isaac did not become a tanner as his grandfather and father had. Nor did he propose to better them. Unlike James Jones, who turned his house into a tavern and planned to build a merchant or grist mill using water from the White Clay Creek,42 Isaac simply identified himself as a "yeoman" and his property as his "farm."43 Isaac was not remembered for being "an active member of New Garden Mo. M't'g" like his brother Joseph. In fact, Isaac was not even married at a Quaker meeting. He and Margaret Johnson were wed at Old Swedes' Church in Wilmington, Delaware.44

Isaac Sharp did not become a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly like his father or his brother Joseph.45 He did not purchase quarrying tools and begin mining feldspar like Joseph. Nor did he invest in surveying instruments, globes, and maps or found The Farmers' Library of London Grove as Joseph did.46 Isaac was much more content.

Isaac Sharp and his wife Margaret lived in a good-size, two-story log house that was constructed of un-hewn logs. It was certainly not the worst house in New Garden Township. While Isaac Sharp's house was assessed at $30 in 1802, other area houses were assessed as low as $15. However, Isaac and Margaret's house was not the best either. Houses in New Garden Township could be valued as high as $65 or $75. In neighboring London Grove Township, where dwellings tended to be assigned higher values, Samuel Sharp's house and the house that once belonged to James and Abigail Jones were both assessed at $90. On a continuum with one end defined by these large masonry dwellings and the other small "log cabins," Isaac and Margaret Sharp's sizable log house was assigned a value that was only slightly below the midpoint.

The choices that Isaac and Margaret Sharp made in opting for a "middling" dwelling were echoed throughout their material world. Isaac and Margaret did not own a barn; they owned a stable.47 They did not have an eight day clock or a desk and bookcase in their house, nor did they inherit the large dining table that had once belonged to Isaac's grandfather Joseph.48 However, Isaac and Margaret Sharp were not without comforts. At Isaac's death in 1825, they owned five beds and bedsteads, a looking glass, and even carpet.49 The small window openings that lit the first-floor of their house were actually fitted with glazed sash windows, and the interior walls, which were once only white-washed, had seen their first coat of plaster. Although Isaac and Margaret's house was not the "sylvan hideaway" it later was for the Crowells,50 it did serve as the setting for their unassuming and otherwise easily forgotten lives.

1 James Crossan, administrator for the late Isaac Sharp, advertised Isaac Sharp's property in The Village Record on November 9, 1841. The property was to be sold pursuant to an order of the Orphans' Court of Chester County on December 24. Newspaper clippings file, New Garden Township lands, Chester County Historical Society Library (North High Street, West Chester, Pennsylvania).

2 The history of London Grove Township is recounted in J. Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope, History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881), 183.

3 Futhey and Cope, 187; and Chester County Deed Book E, page 55 (sale from William Penn, Jr. to Joseph Sharp). Chester County Archives and Records Center (Westtown Road, West Chester, Pennsylvania).

4 Joseph Sharp's signature was present on the petition to the Justice of the Peace of Chester County that requested the formation of London Grove Township. A photocopy of this document was provided to the author by Shirley Rosazza, former member of the historic preservation board for London Grove Township.

6 The date 1737 is based on a datestone on the still extant Joseph and Mary Sharp House (see figure 5).

7 Will of Joseph Sharp (written 1746). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #1012. Samuel Pyle's name is spelled "Pile" in the will.

8 The Sharps of Chester County, Pennsylvania, and Abstracts of Records in Great Britain (Seymour, CT: W.C. Sharpe, 1903), 16; and Futhey and Cope, 551.

9 Isaac Sharp and Margaret Johnson were married in 1781. The Sharps of Chester County, 17.

10 The 1783 Pennsylvania state tax assessments included a count of how many people occupied each property in New Garden Township. Chester County Archives and Records Center.

11 Will of Joseph Sharp (written in 1746). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #1012.

12 Chester County Deed Book G2, page 340; and Chester County Deed Book M2, page 318. Chester County Archives and Records Center.

13 Will of Isaac Sharp (written 1824). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #7602.

14 Account in probate records for Isaac Sharp. Chester County Archives and Records Center, #10167.

15 Will of Joseph Sharp (written 1844). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #11207.

16 Chester County Deed Book R6, page 366. Chester County Archives and Records Center.

17 Chester County Deed Book S6, page 486; and Chester County Deed Book Y8, p. 313. Chester County Archives and Records Center.

18 James W. Crowell, "Recollections of Life on the Crowell Farm," in William Innes Homer, ed., Eakins at Avondale and Thomas Eakins, a Personal Collection (Chadds Ford, PA: Brandywine Conservancy, c. 1980), 15; and William Innes Homer, "Eakins, the Crowells, and the Avondale Experience," in Eakins at Avondale, 33, note #9.

19 I wish to thank all those who aided in the field work for this project: Bernard Herman, Gabrielle Lanier, Jack Crowley, Leonard Orlando, and Ashli White.

20 Margaret B. Schiffer, Chester County, Pennsylvania Inventories, 1684-1850 (Exton, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 1974), 187-188, 209, 210-211.

21 Ibid, 187-188, 201, 204-206.

22 Inventory for the Isaac Sharp (taken 1825). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #7602.

23 Although any hard

evidence would have been obliterated by later additions and by

the demolition of a large section from the back of the structure

prior to the study, there are still some suggestions that there

was once a one-pile structure with a fireplace that was later

partially replaced

or enlarged: the roof pitch, the fireplace placement, the

foundation, and the framing. It is likely that at least parts of

this kitchen were incorporated into the later addition rather

than being completely removed.

24 Both the original log house and the frame addition may have been completely coated with stucco. Once again, because part of the addition has been demolished, much information about that part of the building has been lost.

25 James W. Crowell, "Recollections of Life on the Crowell Farm," in Eakins at Avondale, 15.

26 William Innes Homer, "Eakins, the Crowells, and the Avondale Experience," in Eakins at Avondale, 12-13.

27 James W. Crowell, "Recollections of Life on the Crowell Farm," in Eakins at Avondale, 15.

29 Evidence of white-wash, Spanish brown, and blue paint can still be seen on the original joists that support the second floor. It is unclear in what order the colors were applied or whether they differentiated certain spaces.

30 Inventory of Isaac Sharp (taken 1825). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #7602.

31 Thaddeus M. Harris, The Journals of a Tour into the Territory Northwest of the Allegheny Mountains (Boston: Manning & Loring, 1805), 15 as cited in Terry Jordan and Matti Kaups, The American Backwoods Frontier, An Ethnic and Ecological Interpretation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1989), 175.

32 Benjamin Rush, "An Account of the Progress of Population, Agriculture, Manners, and Government in Pennsylvania, in a Letter from a Citizen of Pennsylvania, to His Friend in England," Columbian Magazine; or, Monthly Miscellany 1:3 (November 1786), 117.

35 Acreage listed in Chester County Deed Book E, page 55; and the will of Joseph Sharp (written 1746). House and other buildings detailed in the will of Joseph Sharp. Chester County Archives and Records Center, #1012.

36 Samuel Sharp is listed as a tanner in Chester County Deed Book G2, page 340. Chester County Archives and Records Center.

37 Accessible Archives, The Pennsylvania Gazette, CD-ROM edition, Folio 2 (1766-1783), (Malvern, PA: Accessible Archives, 195), 7 April 1766, 16 July 1767, and 30 July 1767.

38 Will of Samuel Sharp (filed 1819). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #6713.

39 Will of Joseph Sharp (written 1844). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #11207.

40 Chester County Deed Book M2, page 318. Chester County Archives and Records Center.

41 The Sharps of Chester County, 16.

42 James Jones was given specific rights to water from the White Clay Creek in the 1792 deed from Samuel and Mary Sharp to Isaac Sharp. These water rights hinged on the fact that Jones intended to build a merchant or grist mill and needed to create a dam and race to power the mill. See Chester County Deed Book G2, page 340.

43 Isaac is identified as a "yeoman" in Chester County Deed Book G2, page 340. He refers to his property as a "farm" in his will (written 1824). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #7602.

44 The Sharps of Chester County, 17.

45 Futhey and Cope, 380. Samuel Sharp was elected to the Assembly in 1792. Joseph Sharp was elected in 1815, 1816, 1817, and 1818.

46 "Quarrying tools," "Surveying Instruments," a "Globe," and a "Map of the United States" were included in the inventory of Joseph Sharp (taken 1847). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #11207. The quarrying of feldspar of the Sharps' property is documented in James W. Sharp, "Recollections of Life on the Crowell Farm" in Eakins in Avondale, 16. Joseph Sharp's involvement with the Farmers' Library of London Grove is documented in Futhey and Cope, 310.

47 Chester County Triennial Taxes show the Sharps with a log stable (and no barn) in 1802, 1805, 1811, and 1814.

48 Samuel and Joseph's inventories (dated 1819 and 1847) both included an eight day clock and a desk and bookcase. In Samuel's will, he specifically bequeathed "the large Dining Table that was his Grand Fathers" to his son Joseph. Chester County Archives and Records Center, (Samuel) #6713 and (Joseph) #11207.

49 Inventory of Isaac Sharp (taken 1825). Chester County Archives and Records Center, #7602.

50 James W. Crowell, "Recollections of Life on the Crowell Farm," in Eakins at Avondale, 15.

The surviving Isaac and Margaret Sharp house and the nearby Joseph and Mary Sharp house provided much of the information needed to complete this paper. Other important documents, such as deeds, tavern petitions, and probate, tax and court records, are part of the public record and are housed at the Chester County Archives and Records Center, Chester County Government Services Center, Westtown Road, West Chester, Pennsylvania. Information obtained from the later group of records is specifically cited in the text or in endnotes.

Accessible Archives. The Pennsylvania Gazette, CD-ROM edition. Folio 2 (1751-1765) and Folio 3 (1766-1783). Malvern, PA: Accessible Archives, 1993, 1995.

Atlas of Chester County, Pennsylvania. From Actual Survey by H.F. Bridgents, A.R. Witmer and Others. Safe Harbor, PA: A.R. Witmer, 1874.

Breou's Official Series of Farm Maps, Chester County, Pennsylvania, Compiled, Drawn, and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys. Philadelphia: W.H. Kirk & Co., 1883.

Futhey, J. Smith and Cope, Gilbert. History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881.

Glassie, Henry. "Eighteenth-Century Cultural Process in Delaware Valley Fold Building." Winterthur Portfolio 7 (1972): 29-57.

Herman, Bernard L. "The Model Farmer and the Organization of the Countryside." In Catherine E. Hutchins, ed. Everyday Life in the Early Republic. Winterthur, DE: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1994.

Homer, William Innes, ed. Eakins at Avondale and Thomas Eakins: A Personal Collection. Chadds Ford, PA: Brandywine Conservancy, 1980.

Jordan, Terry G. American Log Buildings, an Old World Heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Jordan, Terry G. and Kaups, Matti. The American Backwoods Frontier, an Ethnic and Ecological Interpretation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Kniffen, Fred B. and Glassie, Henry. "Building in Wood in the Eastern United States: A Time-Place Perspective." In Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach, eds. Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1986.

Lemon, James T. The Best Poor Man's Country, A Geographical Study of Early Southeastern, Pennsylvania. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1972.

Michel, Jack. "'In a Manner and Fashion Suitable to Their Degree': A Preliminary Investigation of the Material Culture of Early Rural Pennsylvania." Working Papers from the Regional Economic History Research Center 5, no. 1 (1981).

Roberts, Warren E. "The Tools Used in Building Log Houses in Indiana." In Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach, eds. Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1986.

Rush, Benjamin. "An Account of the Progress of Population, Agriculture, Manners, and Government in Pennsylvania, in a Letter from a Citizen of Pennsylvania, to His Friend in England." Columbian Magazine; or, Monthly Miscellany 1:3 (November 1786): 117-122.

Schiffer, Margaret B. Chester County, Pennsylvania, Inventories, 1684-1850. Exton, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1976.

-------. Survey of Chester County, Pennsylvania, Architecture: 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries. Exton, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1976.

The Sharps of Chester County, Pennsylvania, and Abstracts of Records in Great Britain. Seymour, CT: W.C. Sharpe, 1903.

The Village Record (newspaper). Advertisement of the Property of the late Isaac Sharp, November 9, 1841. Clipping in Chester County Historical Society Library Newspaper Clippings File, New Garden Township-Lands.